Earlier we tweeted this:

We felt this could use a little context. This is an admittedly abbreviated version of things just to give you a better idea of why Missouri slaves weren’t freed in Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Throughout Civil War history, Missouri had been the ultimate crossroads within the country, both culturally and physically. As evidenced by the battles (1,200, only two other states had more) and general discontent throughout the state, Missouri was a microcosm of the events happening in the United States.

Let’s go back about 40 years before the Civil War even started to see some of the roots of Missouri’s unique place in the Union. Per the Missouri Compromise of 1820, no state north of our southern border (36º 30′) could have slaves except for Missouri itself. Territories west of Missouri were to be free. Confusing? Yes. So even then, Missouri was an unusual geographic area in the Union. (The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 repealed most of the provisions, which would allow each territory to decide the issue of slavery through Popular Sovereignty. Sadly, one of the results was Bleeding Kansas.)

During the Civil War, Missouri was Union, but just barely. The legislature didn’t want to necessarily join the south, but they didn’t want the federal government imposing on the state, either. In June of 1861, Union troops ousted southern-sympathizing Governor Claiborne Jackson. His deposed government reassembled in Neosho, MO, and they voted to secede from the Union that October. However, this “rump” legislature had no official power, but they did have votes in the Confederate Congress. Meanwhile, former Missouri Supreme Court judge (and the Campbells’ Lucas Place neighbor), Hamilton Gamble, was appointed the provisional governor of the state. As requested by President Lincoln, he provided troops for the Union.

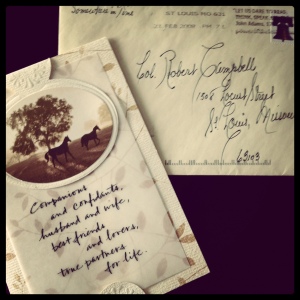

December 17, 1861 loyalty oath signed by Robert Campbell. (Click on it for a larger view.)

Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation only freed the slaves in the ten rebelling states, and Missouri was not one of them. The Emancipation Proclamation did not outlaw the practice of slavery; it was a necessity of war. As Union troops began to occupy the South, they didn’t know what to do with the enslaved people. Were they contraband? Were they free? As you can imagine, the proclamation was controversial. According to the 1857 Supreme Court decision of the Dred Scott case, the federal government did not have the authority to regulate slavery in the territories, so that was problematic. Abolitionists wanted a declaration freeing all the slaves instead of just the slaves in the rebelling states. Slave owners were less-than-pleased because they didn’t receive any compensation. In short, pretty much nobody was happy.

As a representation of the greater country, Missouri was full of infighting and factions, as evidenced by the provisional legislature and the competing rump legislature. The people were just as split with the St. Louis area harboring more pro-Union sentiment than elsewhere in the state. (Case in point: Through a governor-appointed police board, Jefferson City “managed” St. Louis’ police force so they could remotely exert their influence on the city. Today, 150 years after the Civil War, this is still the case.)

As an example of the divisive sentiment that pervaded the Missouri, Robert had to sign many loyalty oaths, like the one pictured above. Robert’s business suffered because he had a hard time collecting money from his customers, and daily operations were often interrupted because of troop occupation in the city and along trade routes, among other things. Meanwhile at home, the route of the infamous march of troops to the arsenal during the Camp Jackson Affair went right behind Campbell House on Olive Street.

But back to the slavery issue. The Thirteenth Amendment ultimately outlawed the practice of slavery on a national level when it was ratified by Georgia in December of 1865.